How are laws made?

Each year, Parliament opens for a new Session. There is no fixed length for a Parliamentary Session; they are usually spring to spring with a number of breaks, called recesses. On the day the Session starts, the reigning monarch will read out a speech written by the Government that sets out its policies and proposed Bills for the new Parliamentary Session. This is known as the “King’s Speech".

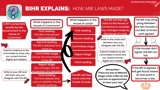

However, this does not mean that these Bills will be law. For a Bill to become a law (or an Act), there are a number of stages that have to be followed. This Explainer will discuss the difference between Bills and Acts and how a law is made.

Watch this explainer as a video Read UK Parliament's Easy Read explainer

What is a Bill?

A Bill is not a law. Rather, it is a proposal for a new law, or a proposal to change an existing law. Existing laws can be changed because of something called parliamentary sovereignty which means that every Parliament is as powerful as the ones before and after it. This means that Parliament cannot make laws which would restrict a future Parliament. Therefore, all laws (including the Human Rights Act) can be changed or replaced.

To become a law, a Bill has to be debated and agreed upon by the two Houses of Parliament: the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The House of Commons is made up of Members of Parliament, known as MPs who are elected by the public to represent local areas (or constituencies). You can find your MP here.

The House of Lords is independent from the House of Commons. Those who sit in the House of Lords are sometimes called peers (or Lords). There are different types of peers; some may be former MPs or representatives of political parties but there are also peers who do not represent a specific political party. You can find out more about the House of Lords here. Both the House of Commons and the House of Lords play a crucial role in making laws. A Bill does not become a law until both the House of Commons and the House of Lords have agreed on the content, and it has been approved by the reigning monarch, currently the King. This approval process is known as Royal Assent.

A Bill can be introduced by the Government, individual MPs or Lords or private individuals or organisations. They can be introduced in either the House of Commons or House of Lords. The most common way a Bill is introduced is by the Government in the House of Commons. These are often Public Bills as they change how the law applies to the general population. Any Bill to change the Human Rights Act would be a Public Bill.

There are also Draft Bills. These are issued for consultation before being formally introduced to Parliament which allows changes to be made before the formal introduction of the Bill. Draft Bills may be examined by select committees from the Commons or Lords or by a joint committee of members from both Houses. Draft Bills can take the form of White Papers which state definite intentions for government policy. They can also take the form of Green Papers which usually put forward ideas for future government policy and are open to public discussion and consultation.

Before a Bill becomes a law, there are a number of stages it has to go through. These stages can take months to complete.

Most commonly, Bills are introduced in the House of Commons. To start the process to become a law, Bills have to be formally introduced in what is known as the first reading. This involves reading the title of the Bill in the House of Commons. It can happen at any time during the Parliamentary Session and does not usually include debate about the contents of the Bill. Following this, the Bill will be published for the first time.

The next stage is the second reading, which is the first opportunity for MPs to debate the main principles of the Bill. The debate will be started by the Government minister, spokesperson or MP responsible for the Bill. The Opposition spokesperson will then respond with their views on the Bill. This will continue the debate, with MPs able to give their views on the new Bill and what they think might be missing. At the end of the debate, the Commons will vote on whether the Bill should proceed to the next stage.

If a Bill passes the second reading, it will then go to the Committee stage. This involves a line-by-line examination of the Bill. Most Bills will be dealt with in a Public Bill Committee. The Committee can hear evidence from experts and interest groups from outside Parliament. The chair of the committee will decide what changes (sometimes called amendments) to the Bill will be discussed. Every part (or clause) in the Bill must be agreed to, changed or removed during this stage. Some parts (clauses) will not be debated.

Some Bills can be fast tracked through the House of Commons. This means that they will receive less consideration and less debate. This happened recently with the Coronavirus Act and led to organisations like BIHR raising serious concerns about the Bill not being properly considered (scrutinised) before becoming a law.

Once a Bill has completed the committee stage, it goes through the report stage. At this point the Bill can be debated by the House of Commons and any further changes can be proposed. If a Bill is particularly complicated or long, this stage of debate could last for several days. All MPs can suggest any amendments or new parts that they think should be added.

After the report stage, the House of Commons has the final debate on the Bill. This is known as the third reading and usually happens immediately after the report stage. This debate is usually shorter than the previous debates and is limited to the current content of the Bill. Any amendments (or changes) cannot be made to a Bill in the Commons at this stage. At the end of the debate, the House of Commons (made up of elected MPs) will vote on whether to approve the Bill. If they do, the Bill will then go to the House of Lords to be scrutinised and debated.

In the House of Lords, the Bill will go through the same stages as it does in the House of Commons. The Lords will have various opportunities to debate the Bill, add any changes (or amendments) and vote on whether the Bill should continue. The third reading in the House of Lords provides the opportunity for the Lords to ‘tidy up’ a Bill, making sure that the eventual law is effective and workable- without loopholes. Unlike in the House of Commons, changes can be made at the third reading in the House of Lords but only if the issue has not been fully considered or voted on previously. Usually, these changes are used to clarify specific parts of the Bill.

The House of Lords can have a powerful impact on Bills from the House of Commons. In the last year in Parliament, they voted against the Government (also referred to as defeating the Government) 129 times. Interventions from the House of Lords in recent weeks have led to important changes in some recent laws.

Following campaigning from the RNIB about the disproportionate impact on disabled people, the House of Lords inserted a clause into the Elections Bill which requires the Electoral Commission to consult groups representing the interests of people affected when creating new guidance. The House of Lords also removed a clause from the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill which would have allowed suspicion-less stop and search after groups like Liberty campaigned that this would “exacerbate discriminatory over-policing of people of colour”.

If there are no amendments to the Bill in the Lords, it will be sent to the monarch for Royal Assent. If there are amendments, the Bill will be sent back to the House of Commons to consider the changes made by the House of Lords.

If a Bill is started in the House of Lords, it will go through all of these stages but in reverse.

What happens next?

After a Bill has been approved by both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, it returns to the House it started in for the changes suggested by the other House to be considered. For a Bill to become law, both Houses must agree on the exact wording of the Bill.

This is where the idea of ‘ping pong’ comes in. As both Houses must agree on the exact wording of the Bill, if any amendments are disagreed with in either House, the Bill will be sent back. For example, if the House of Lords disagrees with an amendment to a Bill started in the House of Commons, they will send the Bill back to the Commons. If the House of Commons then disagrees with the change made by the House of Lords, it will return to the House of Lords. A Bill may therefore go back and forth numerous times between each house (or ping pong) until both Houses agree. Recently, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act ping ponged between the House of Commons and the House of Lords six times before getting Royal Assent and becoming law.

Once the Commons and Lords agree on the final version of the Bill, it can receive Royal Assent and become law, otherwise known as an Act of Parliament. Royal Assent is the Monarch’s (currently the King’s) agreement to make the Bill into an Act and is a formality. The King does not refuse to make Bills into law.

Parliamentary Sessions are what we call the year in Parliament. These normally start in Spring and last for 12 months. The last Parliamentary Session ended on 28th April 2022 and this Session started on 10th May 2022. This is why we saw a number of different Bills become law recently, including the Elections Bill and the Nationality and Borders Bill. If a Bill is not passed into law or carried over to the next session, it will be abandoned.

If the two Houses do not reach agreement, the Bill will fail. However, the House of Lords does not have an absolute veto over Public Bills. The Parliament Acts mean that if a Bill is started in the House of Commons and certain conditions are met, then the Bill can be presented for Royal Assent without the House of Lords approval. These conditions include being rejected by the House of Lords (this means that it has failed to pass through all of its stages in the Lords) for a certain period of time (at least a year). This is very rare and has only been used four times since 1949.

After Royal Assent, implementing the law becomes the responsibility of the Government. The law may start immediately or after a certain date.

Read more about how laws are made by the UK Government. Read more about how laws are made by the Northern Ireland assembly. Read more about how laws are made by Scottish Parliament. Read more about how laws are made in Wales.

Related topics

Find out more about UK human rights law.

Stay up-to-date

Get our newsletter

Get monthly updates on UK human rights law and our work, resources and events sent straight to your inbox.